Landscape Photography

And the art of living on purpose.

Our work, family, and financial needs dictate what gets most of our attention, and the stress this creates is very real.

Treating photography as an intentional act – a practice – uncovers opportunities to relieve stress, reconnect with true ourselves and foster our innate creativity.

Landscape photography elevates this further by encouraging us to venture outside, feel the seasons and see everything anew. For many, it becomes a passion that brings purpose and joy to their otherwise busy, structured lives.

For me, it acts as a balancing force against the relentless demands of modern life and its responsibilities, pressures and stresses.

It lets me interpret things in my own unique way, and then create a record of what I felt and saw.

Whatever aspect appeals to you – the creative, the technical, or just the great outdoors, it offers fabulous scope for personal, technical and artistic expression.

Best of all, it's completely portable, so you'll always have it no matter where you go in the world.

40 Years & Counting

I created my first image over 40 years ago. As an awkward teenager who struggled to fit in with the cool kids, photography was the perfect solo pursuit.

With a camera slung over my neck, foraging down the local creek or the beach – a 10-minute bike ride away – was exciting again! Photography gave me the perfect excuse to spend more time outdoors.

Even back then, I loved waiting for the light and capturing a scene as only I could.

Now in my 50s, that part hasn't changed. However, I'm no longer rushed; I'm not anxious for a result. Matter of fact, I enjoy the process even more than the result.

To see some of my images, check out the gallery.

A story of two beginnings.

Most photographers my age start out the same way: someone (perhaps a thoughtful parent) hands them an old camera, hapless fumbling ensues, followed soon after by an insatiable urge to shoot everything.

My introduction was no different. I was about 12 when my dad handed me his beloved Voigtländer – the camera he'd used decades earlier to document his big lap of Australia. A robust, simple camera of unburstable quality, it taught me to calm my mind and view things with curiosity and intention.

Kodachrome film was expensive back then, and waiting a couple of weeks to see the outcome of your efforts was normal. Like most photographers who started out in the film era, this forced a deliberate, careful approach to composition and metering. Despite the cost, though (and the absence of instant gratification), I photographed everything – from spider webs and sunsets to motorbikes and people. I funded my passion by selling stray balls collected along the boundary of the local golf course, plus letter openers I'd craft from six-inch nails.

First Sales

Me and my first bike – a Honda XR-75

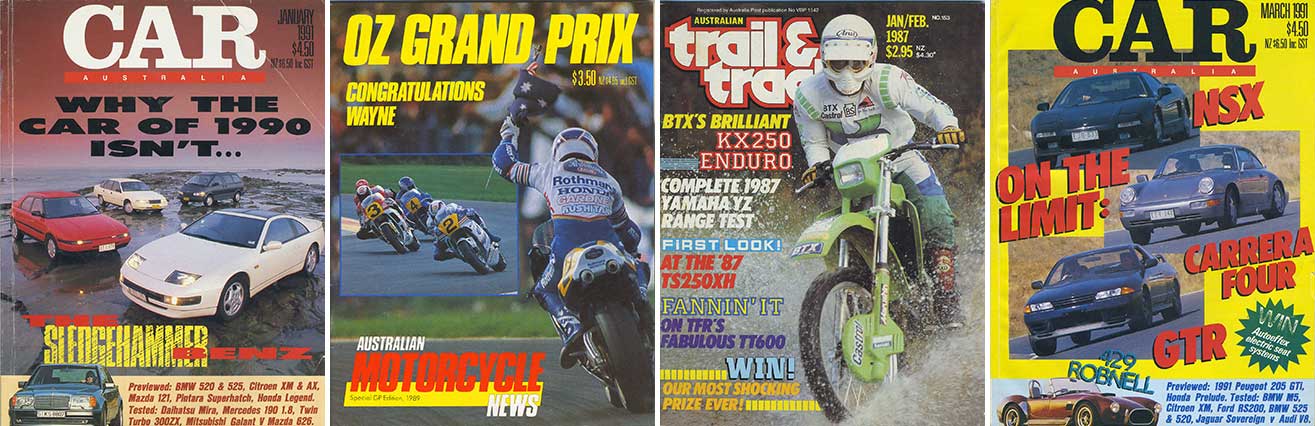

The Seaford motorbike track yielded my first saleable images, mostly to proud parents of young riders. One day, a strange character in a Bedford van rolled up and thrust a few rolls of Tri-X 400 in my hand with an encouraging, “Show me what you can do, kid.” His name was Les Swallow, and he owned my favourite magazine – Trail & Track.

A few months later, at the age of 14, my first article appeared in print. Others followed, and I was eventually offered a full-time gig with the company that later acquired Les's rag.

Turning Pro

I went on to shoot for a stable of motoring titles like Car Australia (then MOTOR), 4×4 Australia, AMCN, and a smattering of others – plus a handful of car manufacturers and freelance clients. It was a wild period of race tracks, motorsport royalty, luxury resorts and exotic cars in amazing locations. Sadly, it was the time before smartphones and selfies, so I have almost no photographs of myself throughout that decade.

Although I shot a metric tonne of exotic cars, famous racers and gorgeous motorcycles, my true love was always landscapes. Getting outside, holding a camera and slowing down offered solitude to a young man still trying to figure out who he was. At times, it would be the only thing that stopped me going crazy. Indeed, if it weren't for an art director who convinced me to leave my first job in banking to join Syme Magazines, I probably would have had several heart attacks by now. Or died of alcoholism. I was good at banking, but it was a soul-crushing job that left me anxious and miserable.

Photography, on the other hand, was immersive, exciting and liberating. It allowed me to create something that no one could replicate. To conceive and capture an idea; to freeze a moment in time was thrilling, and it remains so to this day.

Photography 2.0

Me and my kids – reason enough to smile!

Following two decades of highs and lows (career and business success, divorce and financial collapse, midlife crisis, remarriage and financial reparation), I picked up a camera again in 2020.

Within a few short weeks, I realised how much I'd missed it. But unlike my early days of striving to ‘get the shot', my experience now was all about slowing down again, being present, and enjoying time amongst nature.

Venturing outside, walking slowly and really seeing your surroundings is an elixir for the modern life. Whether you make an image or not is secondary – it's the act that matters. I think my images today are better for it, too.

Landscape photography is therapeutic, both physically and mentally. It gets us out of the house and out of our head. It engages our left and right brain simultaneously – the technical and creative – so that our subconscious can rise above the noise and work quietly to resolve whatever plagues us.

I've recently added car photography back into the mix, and free of commercial pressures, it has brought a fresh dimension to my outdoor photography; allowing me to combine two great loves – the landscape, and motor vehicles.

And so once again, photography has saved my life – gently coaxing me to breathe again, appreciate my surroundings, and freeze a fresh new set of moments.

It's good to be back.

Get my sporadic emails containing ideas &

questions on photography, midlife & creativity.

All content © Copyright 2025 Peter Fritz | Contact